The Birth of Castle Bytham

Before the name, before the stone, there was a valley quiet, deep, and ancient. The Anglo-Saxons called it Bythme, meaning “bottom of the valley.” It was a place of stillness, where deer wandered through mist and the land held its breath.

Then came the Normans.

In the wake of the 1066 conquest, William the Conqueror rewarded his loyal barons with land. One of them, Drogo de la Beuvrière a Flemish noble looked upon the valley and saw not silence, but strategy. He built a castle here, first of timber, then of stone. It rose above the vale like a crown of vigilance, watching the roads between Stamford and Lincoln.

The village that grew around it took its name: Castle Bytham the castle in the valley.

But this was no passive place. In 1221, during the Barons’ War, William de Forz, Count of Aumale, seized the castle in rebellion against King Henry III. The king responded with fury. Siege engines rolled across the hills. For days, the fortress resisted. Then the walls fell, and the castle was dismantled — not by time, but by royal decree.

Even in ruin, Castle Bytham remained a place of significance. In the 14th century, John of Gaunt, Duke of Lancaster, sent his children to be raised here. Among them was Henry Bolingbroke — the boy who would become King Henry IV of England. A future monarch played among broken stones and fading banners.

Centuries passed. The castle faded into the earth, its stones repurposed for homes and farms. But the village endured, shaped by memory and resilience.

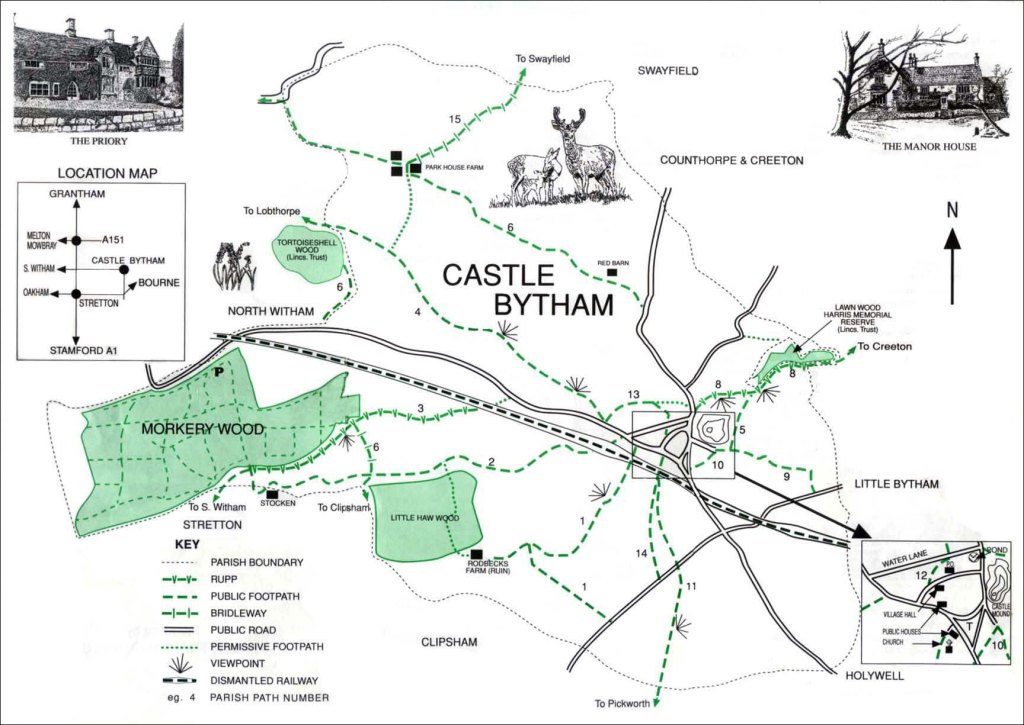

During World War II, the nearby Morkery Wood became a munitions depot. In 1942, a Halifax bomber from the Royal Air Force crashed into the forest, leaving behind a scar that still whispers in the trees.

Traditions, too, survived. May Day celebrations, once banned during the Puritan era, returned with joy. Legend says the old maypole, hidden from view, was later used as a staircase in the church tower a quiet defiance carved into wood and stone.

Castle Bytham is not just a name. It is a story of conquest and rebellion, of royalty and resilience. It is a place where the valley became a fortress, and where every stone still speaks.

Castle Bytham and the Crown That Never Touched It

Castle Bytham stands quietly in the Lincolnshire landscape, its name echoing through centuries of English history. With its ruined castle, royal connections, and medieval charm, it’s easy to imagine kings and queens shaping its fate. But when it comes to King Richard III, the truth is simpler and more distant.

Richard III, the last Plantagenet king, was born in 1452 and ruled England from 1483 until his death at the Battle of Bosworth in 1485. His story is one of ambition, controversy, and tragedy. Yet despite his dramatic reign, he had no direct role in the founding or early development of Castle Bytham.

The village’s origins stretch much further back. In the Domesday Book of 1086, the area was recorded as West Bytham. At that time, there was no castle only a settlement nestled in a valley known as Bythme, meaning “bottom of the valley” in Old English. It was after the Norman Conquest that the landscape changed.

Shortly after 1066, a Flemish baron named Drogo de la Beuvrière was granted land by William the Conqueror. Drogo built a castle on the hill above the valley, transforming the settlement into a fortified site. The village became known as Castle Bytham

the castle in the valley. Over time, it grew in importance, hosting noble families and even serving as a childhood home for Henry Bolingbroke, who would become King Henry IV.

By the time Richard III was born, Castle Bytham’s castle was already in ruins. It had been dismantled in 1221 after a rebellion against King Henry III. Though the village remained active and historically rich, it was no longer a seat of power or royal residence.

Richard III’s connections to Lincolnshire were real — he had influence in the region and ties to other castles, such as Fotheringhay, where he was born. But Castle Bytham was not part of his story. Its foundation belonged to an earlier age, shaped by Norman ambition and medieval conflict, not by the last king of the House of York.

So while Castle Bytham may stir royal imagination, its stones were never laid by Richard’s hand. They whisper of other kings, other battles, and a legacy that began long before his crown was ever forged.

Monarchs Who Touched Castle Bytham

Castle Bytham may seem like a quiet village tucked into the Lincolnshire countryside, but its stones remember kings. Not all monarchs left their mark here and some, like Richard III, never did. Yet others shaped its fate in ways that still echo through the ruins.

It began with conquest.

After the Norman victory in 1066, William the Conqueror rewarded his loyal barons with land. Among them was Drogo de la Beuvrière, a Flemish noble who built a castle above the valley known as Bythme. The settlement that grew around it became Castle Bytham the castle in the valley. Though William himself never lived here, his hand guided its birth.

Later, in the 13th century, Castle Bytham became a rebel’s refuge. William de Forz, Earl of Aumale, seized the castle during the Barons’ War. In 1221, King Henry III responded with force. Siege engines rolled across the hills, and after days of resistance, the castle fell. Henry ordered it dismantled not by time, but by royal decree. His decision reshaped the village’s future.

Then came a quieter kind of royalty.

In the 14th century, John of Gaunt, Duke of Lancaster and son of King Edward III, sent his children to be raised in Castle Bytham. Among them was Henry Bolingbroke the boy who would become King Henry IV. A future monarch played among broken stones and fading banners, giving the village a rare and direct link to the English crown.

Though Henry V never lived in Castle Bytham, his grandmother, Lady Alicia Basset, did. She was one of the wealthiest women in England and a resident of the village in the late 1300s. Her presence added another thread to the royal tapestry.

Other noble figures passed through: Thomas, Duke of Clarence; John, Duke of Bedford; Humphrey, Duke of Gloucester — all sons of Henry IV. Sir Walter de Hungerford, steward to John of Gaunt, also held ties to the village.

By the time Richard III was born in 1452, Castle Bytham’s castle was already in ruins. The village remained, shaped by memory and resilience, but it was no longer a seat of power. Richard’s story belonged to another chapter of English history dramatic, tragic, but not entwined with this valley.

Castle Bytham’s royal legacy is quiet but real. It was never a palace, never a court. But it was a cradle of rebellion, of childhood, of noble blood. And in its earthworks and echoes, the past still speaks.